Bacterial transformation is a cornerstone technique in molecular biology, biotechnology, and genetic engineering. It allows researchers to introduce foreign DNA into bacterial cells, enabling DNA cloning, gene expression, and large-scale protein production. Among the different transformation techniques available, the heat shock method remains one of the most widely used due to its simplicity, affordability, and reliability—especially when working with Escherichia coli (E. coli).

This article provides a detailed, step-by-step educational overview of bacterial transformation using the heat shock technique. It explains the biological principle, laboratory procedure, applications, and downstream uses, making it ideal for undergraduate students, graduate trainees, and early-career researchers.

What Is Bacterial Transformation?

Transformation is the process by which a bacterial cell takes up extracellular DNA from its environment. This DNA can then be maintained, replicated, or expressed inside the cell.

In nature, some bacterial species are naturally competent, meaning they can spontaneously absorb DNA. However, many commonly used laboratory strains—such as E. coli—require artificial induction of competency.

Cells capable of taking up DNA are referred to as competent cells. In molecular biology laboratories, competency is typically induced using chemical or physical methods.

What Is Heat Shock Transformation?

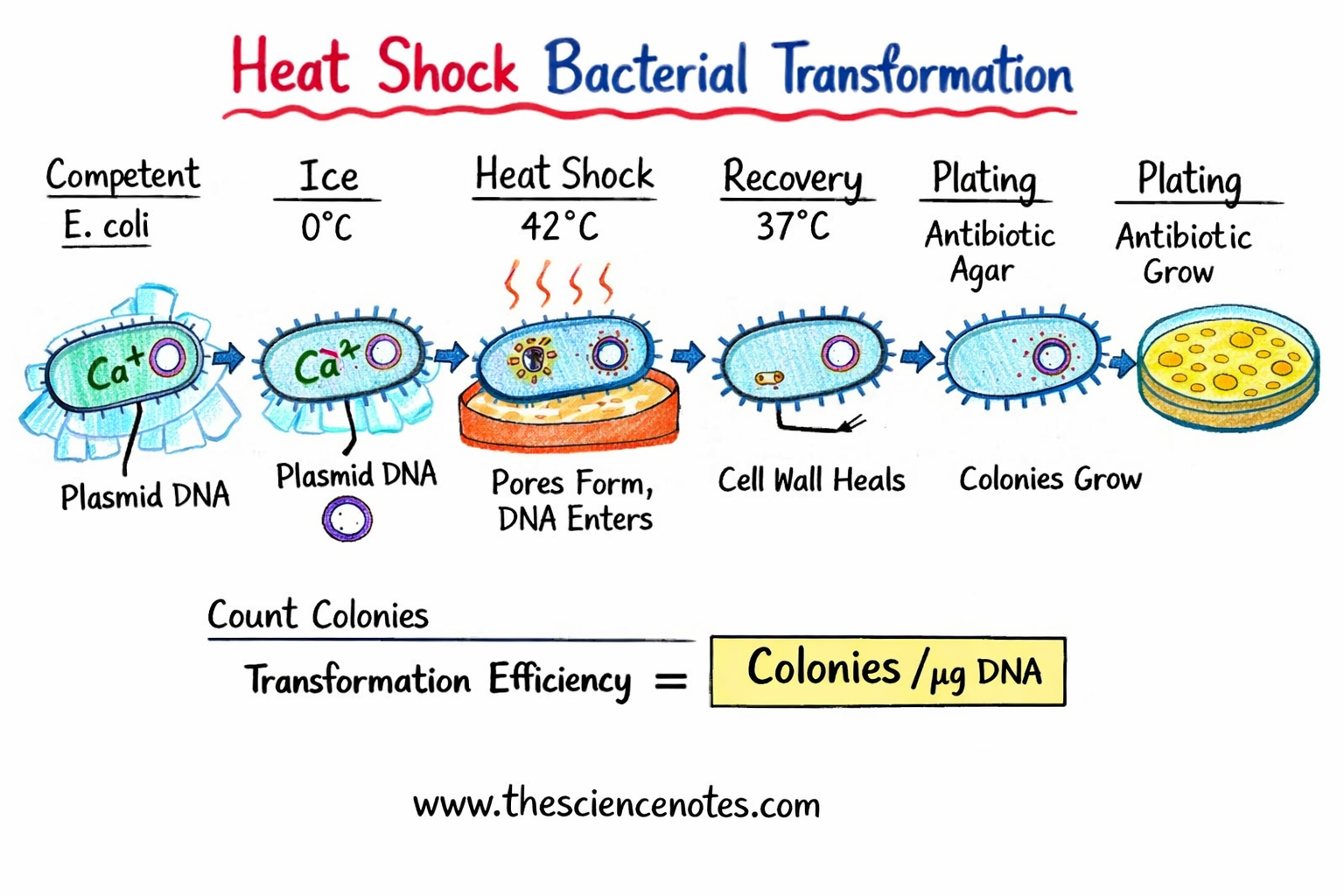

Heat shock transformation is an artificially induced method that temporarily increases the permeability of the bacterial cell membrane, allowing plasmid DNA to enter the cell.

Core Principle

Bacterial cells are exposed to a calcium-rich environment, usually calcium chloride (CaCl₂).

Calcium ions neutralize the negative charges on both the plasmid DNA and the bacterial cell surface.

A brief exposure to high temperature (42°C) creates a thermal and pressure imbalance across the membrane.

This imbalance leads to the formation of temporary pores, through which plasmid DNA enters.

When cells are returned to cold or physiological temperature, the membrane reseals.

Plasmids: The DNA Molecules Used in Transformation

The most commonly used DNA in bacterial transformation experiments is the plasmid.

What Is a Plasmid?

A plasmid is a small, circular, double-stranded DNA molecule that exists independently of the bacterial chromosome. Plasmids can supercoil, which reduces their size and makes them more likely to pass through membrane pores during transformation.

Essential Features of a Plasmid

1. Multiple Cloning Site (MCS)

The multiple cloning site contains short DNA sequences recognized by restriction endonucleases. These enzymes cut DNA at specific sites, allowing researchers to insert a gene or DNA fragment of interest into the plasmid.

2. Origin of Replication (ORI)

The origin of replication tells the bacterial cell where to begin copying the plasmid. Without a functional ORI, the plasmid cannot be maintained inside the cell.

3. Antibiotic Resistance Gene

Most plasmids include a gene that provides resistance to a specific antibiotic (such as ampicillin or kanamycin). This feature enables selection, ensuring that only bacteria containing the plasmid survive on antibiotic-containing media.

Competent Cells: Preparing Bacteria for DNA Uptake

Why E. coli Is Commonly Used

E. coli is the preferred organism for transformation because it:

Grows rapidly

Is genetically well characterized

Is easy to culture and manipulate

Produces high plasmid yields

Chemical Competency Using Calcium Chloride

Competency is induced by exposing bacterial cells to cold calcium chloride:

Calcium ions shield negative charges on DNA and the bacterial membrane

Electrostatic repulsion is reduced

The cell wall becomes more permissive to DNA entry

Cells are kept on ice throughout this process to stabilize the membrane before heat shock.

Mechanism of Heat Shock Transformation

The transformation process involves several coordinated steps:

DNA Binding

Plasmid DNA associates with the bacterial surface during cold incubation.Thermal Shock

A rapid shift to 42°C creates a pressure difference across the membrane.Pore Formation

Temporary pores form in the membrane.DNA Entry

Supercoiled plasmid DNA enters the cytoplasm.Membrane Recovery

Cooling allows the membrane to reseal, trapping DNA inside.

Step-by-Step Heat Shock Transformation Protocol

Preparation and Sterility

Clean the workspace thoroughly

Sterilize all solutions and instruments

Prepare LB media and LB agar plates

Add antibiotics to agar at 50–55°C

Allow plates to solidify at room temperature

Pre-warm antibiotic plates to 37°C

Set water bath to 42°C

Transformation Procedure

Thaw chemically competent E. coli cells on ice

Add 1–5 µL of cold plasmid DNA (≈1 ng/µL)

Gently mix and incubate on ice for 30 minutes

Heat shock cells at 42°C for 30 seconds

Immediately return tubes to ice

Add 450 µL of recovery medium

Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour with shaking (>225 rpm)

Plate 20–200 µL of transformed cells onto LB agar with antibiotic

Incubate plates overnight at 37°C, inverted

Selection and Identification of Transformants

After overnight incubation, bacterial colonies appear on antibiotic plates.

Why Antibiotic Selection Works

Only cells that have successfully taken up the plasmid—and therefore express the antibiotic resistance gene—can grow. Non-transformed cells are eliminated.

Calculating Transformation Efficiency

Transformation efficiency measures how effective the transformation was.

Formula:

Transformation Efficiency =

(Number of colonies × dilution factor) ÷ DNA plated (µg)

This metric is essential for comparing different protocols, plasmids, or competent cell batches.

Preparing Chemically Competent Cells (Overview)

Grow bacteria to mid-log phase (measured by optical density)

Chill cells on ice to halt growth

Centrifuge at 4°C and discard supernatant

Wash cells multiple times with cold 0.1 M CaCl₂

Final resuspension in CaCl₂ + 15% glycerol

Aliquot into microcentrifuge tubes

Store at −80°C

Alternative Transformation Methods

Electroporation

Electroporation uses a brief electric pulse to create membrane pores. It offers higher efficiency but requires specialized equipment and salt-free DNA preparations.

Blue-White Screening

Many plasmids contain the lacZ gene encoding β-galactosidase:

Blue colonies: plasmid without insert

White colonies: plasmid with inserted DNA

This method simplifies screening for recombinant clones.

Applications of Bacterial Transformation

Bacterial transformation enables:

DNA cloning and plasmid amplification

Gene expression studies

Recombinant protein production

Functional genomics

Structural biology and crystallography

Downstream Applications After Transformation

Plasmid Purification

Transformed bacteria are grown in liquid media with antibiotics. Plasmids are isolated using commercial purification kits.

Protein Expression and Purification

In expression experiments:

Bacteria produce large amounts of protein

Cells are lysed

Target proteins are purified using affinity chromatography

Proteins may be crystallized for structural analysis

Conclusion

The heat shock method of bacterial transformation is a foundational technique that underpins modern molecular biology. By combining chemically competent cells, calcium chloride, and a brief thermal shock, researchers can efficiently introduce plasmid DNA into bacteria.