Microplastics, defined as plastic particles smaller than 5 mm in diameter, have emerged as pervasive environmental contaminants of global concern. Generated through both intentional production and the fragmentation of larger plastic debris, microplastics are now detected across marine, freshwater, terrestrial, and atmospheric environments. Their persistence, physicochemical heterogeneity, and capacity to interact with biological systems raise significant concerns regarding ecosystem integrity and human health. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the sources, environmental distribution, transport pathways, and ecotoxicological impacts of microplastics, with particular emphasis on their role as vectors for chemical and biological contaminants. Emerging evidence regarding human exposure routes and potential health implications is critically examined. Despite rapid advances in microplastics research, major knowledge gaps remain, particularly concerning long-term toxicological effects, nanoplastics, and standardized analytical methodologies. Addressing microplastic pollution will require coordinated interdisciplinary research, robust regulatory frameworks, and sustainable material innovation.

Keywords: Microplastics; Plastic pollution; Environmental fate; Ecotoxicology; Human health; Nanoplastics

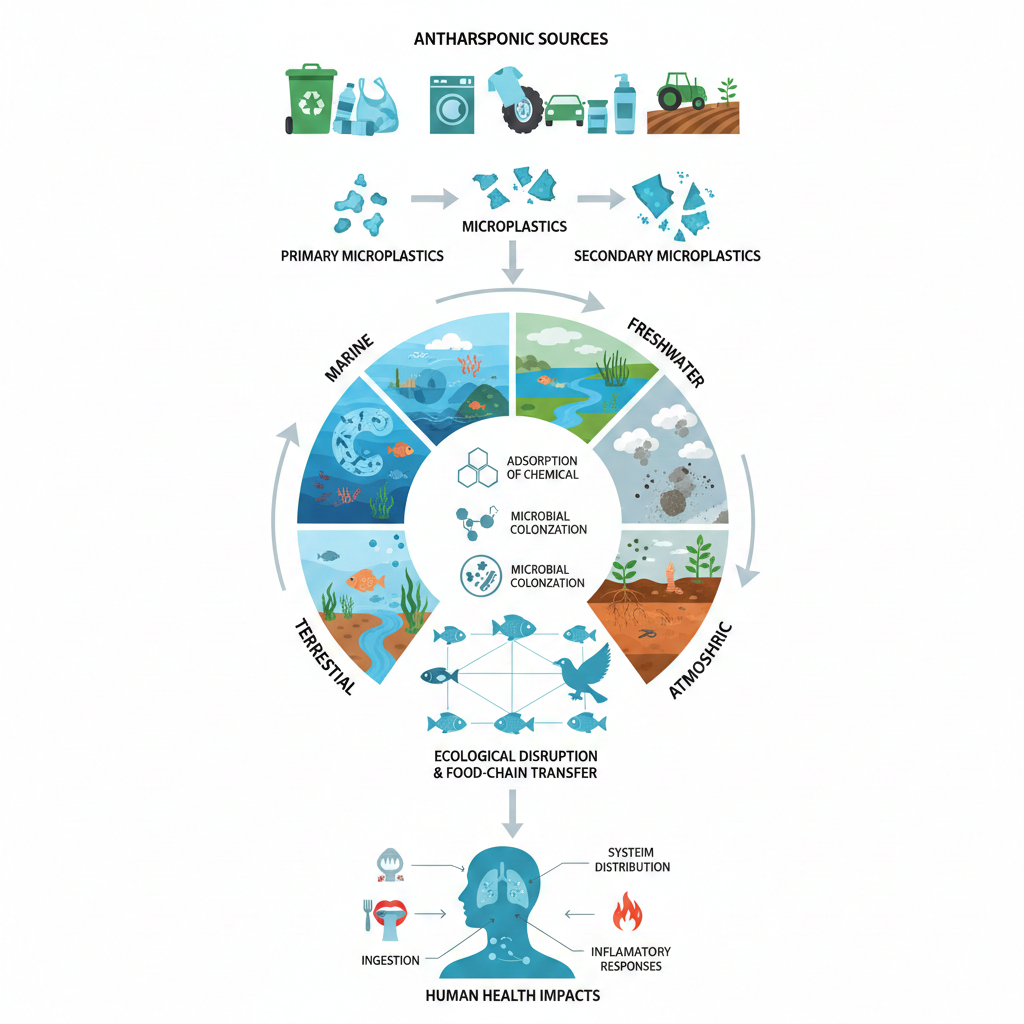

Graphical Abstract

Description:

The graphical abstract illustrates the lifecycle of microplastics from anthropogenic sources to ecological and human health impacts. Primary and secondary microplastics originate from plastic waste, synthetic textiles, tire wear, cosmetics, and agricultural activities. These particles are transported through marine, freshwater, terrestrial, and atmospheric compartments, where they interact with organisms across trophic levels. Microplastics adsorb chemical pollutants and support microbial colonization, facilitating ecological disruption and food-chain transfer. Human exposure occurs through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact, with emerging evidence of systemic distribution and inflammatory responses.

1. Introduction

The widespread adoption of plastic materials since the mid-20th century has fundamentally reshaped industrial production, consumer behavior, and global economies. Annual plastic production has increased exponentially, surpassing hundreds of millions of tons per year. While plastics offer durability, versatility, and low cost, these same properties contribute to their environmental persistence. As plastics degrade, they do not mineralize but instead fragment into progressively smaller particles, leading to the formation of microplastics.

Microplastics were initially recognized as a marine pollution issue; however, subsequent research has revealed their presence across all environmental compartments, including freshwater systems, soils, and the atmosphere. Their detection in remote environments and human biological samples has intensified concerns regarding chronic exposure and long-term health risks. This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of current understanding of microplastic pollution, emphasizing environmental fate, biological impacts, and implications for human health.

2. Definition and Classification of Microplastics

Microplastics are plastic particles smaller than 5 mm, encompassing a diverse range of shapes, sizes, polymer types, and surface chemistries. Common polymer compositions include polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

2.1 Primary Microplastics

Primary microplastics are intentionally manufactured at microscopic sizes for industrial and commercial applications. These include microbeads used in personal care products, industrial abrasives, and pre-production plastic pellets (nurdles). Their small size allows them to bypass wastewater treatment processes, leading to direct environmental release.

2.2 Secondary Microplastics

Secondary microplastics arise from the fragmentation of larger plastic debris through ultraviolet radiation, mechanical abrasion, oxidation, and thermal stress. Packaging materials, fishing gear, disposable plastics, and synthetic textiles represent major sources of secondary microplastics and account for the majority of environmental contamination.

3. Sources and Pathways of Microplastic Pollution

3.1 Plastic Waste Mismanagement

Inadequate waste management practices represent the largest contributor to microplastic generation. Plastics discarded in open environments undergo gradual fragmentation, releasing microplastics into aquatic and terrestrial systems.

3.2 Synthetic Textiles

Synthetic fibers shed from clothing during washing represent a dominant source of microplastics in freshwater and marine environments. Wastewater treatment plants capture only a fraction of these fibers, allowing substantial release into natural ecosystems.

3.3 Tire Wear Particles

Tire abrasion during vehicular use produces microplastic-rich particles composed of synthetic rubber and additives. These particles accumulate on road surfaces and are transported via stormwater runoff into rivers and coastal waters.

3.4 Agriculture and Industry

Plastic mulch films, irrigation infrastructure, greenhouse materials, and sewage sludge used as fertilizer contribute significantly to soil microplastic contamination, with potential implications for terrestrial ecosystems and food production.

Table 1. Major Sources of Microplastics and Environmental Pathways

| Source | Examples | Environmental Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Plastic waste | Bottles, packaging | Marine, soil |

| Textiles | Polyester fibers | Freshwater, marine |

| Tire wear | Synthetic rubber | Urban runoff |

| Cosmetics | Microbeads | Wastewater |

| Agriculture | Mulch films | Soil |

4. Environmental Distribution and Fate

4.1 Marine and Freshwater Systems

Microplastics are widely distributed throughout marine and freshwater environments. Their vertical and horizontal distribution is influenced by polymer density, biofouling, hydrodynamic conditions, and sedimentation processes. In aquatic systems, microplastics are readily ingested by organisms at multiple trophic levels.

4.2 Terrestrial and Soil Environments

Soils are increasingly recognized as major sinks for microplastics. Accumulation in soils alters physical structure, porosity, and microbial community composition, potentially disrupting nutrient cycling and plant productivity.

4.3 Atmospheric Transport

Atmospheric microplastics originate from synthetic textiles, urban dust, and industrial emissions. Long-range atmospheric transport enables deposition in remote environments and represents a direct inhalation exposure pathway for humans.

Table 2. Environmental Compartments Contaminated by Microplastics

| Compartment | Characteristics | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Marine | High accumulation | Food chain transfer |

| Freshwater | Transport pathways | Drinking water risk |

| Soil | Long retention | Altered fertility |

| Atmosphere | Long-range transport | Inhalation exposure |

5. Ecotoxicological Effects of Microplastics

5.1 Physical Impacts

Ingestion of microplastics can cause physical injury, intestinal blockage, reduced feeding efficiency, and false satiation, leading to impaired growth, reproduction, and survival in exposed organisms.

5.2 Chemical Toxicity

Microplastics adsorb environmental contaminants such as heavy metals, pesticides, and persistent organic pollutants. Plastic additives, including plasticizers and flame retardants, may leach following ingestion, increasing toxicological risk.

5.3 Biological Interactions

Microplastics support microbial biofilms known as the “plastisphere,” which may harbor pathogenic or invasive species, altering ecosystem dynamics and disease transmission.

Table 3. Ecotoxicological Effects of Microplastics

| Effect | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Ingestion | Reduced feeding |

| Chemical | Pollutant adsorption | Toxicity |

| Biological | Biofilm formation | Disease spread |

| Cellular | ROS induction | Inflammation |

6. Microplastics and Human Health

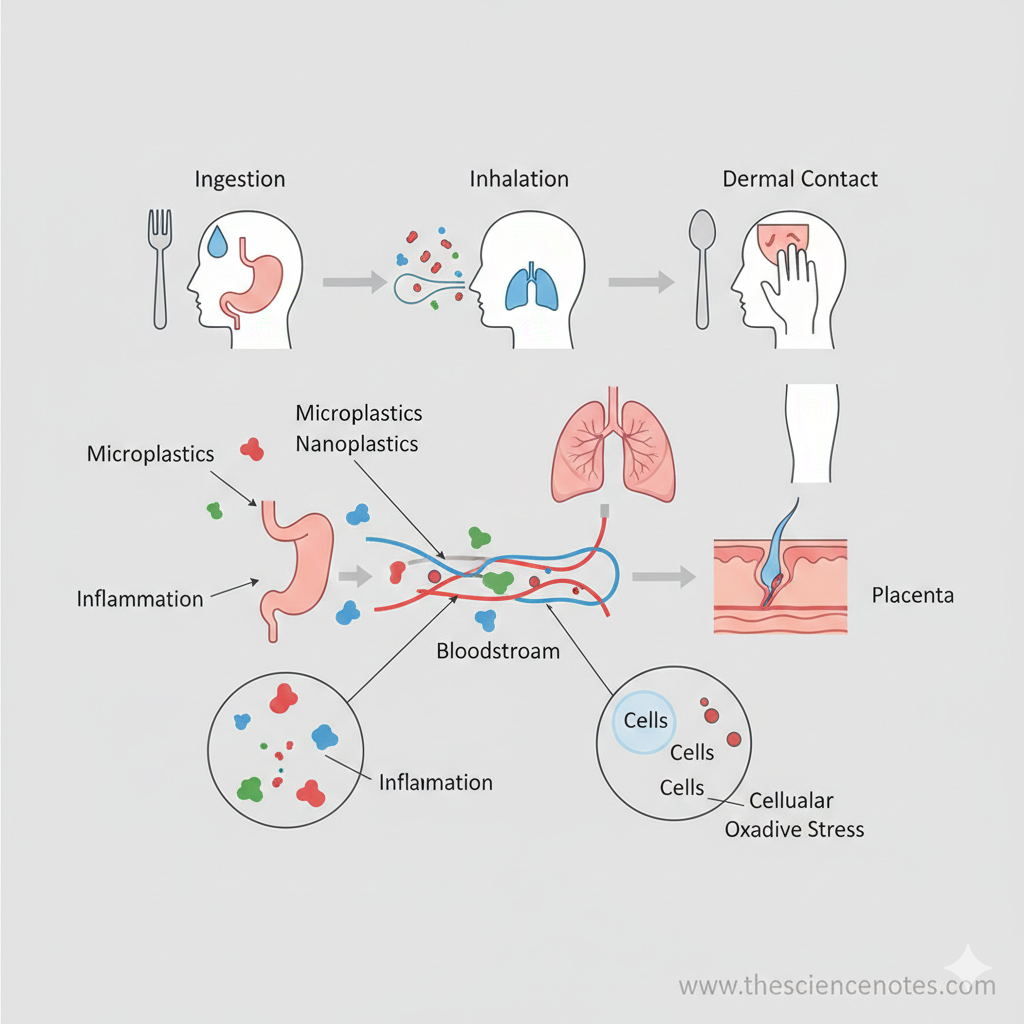

6.1 Exposure Pathways

Human exposure occurs primarily through ingestion of contaminated food and water, inhalation of airborne particles, and dermal contact. Dietary exposure via seafood and drinking water is considered a dominant pathway.

6.2 Potential Health Effects

Experimental studies indicate that microplastics may induce inflammation, oxidative stress, immune dysregulation, and endocrine disruption. Their detection in blood, lung tissue, placenta, and breast milk suggests systemic distribution and potential developmental risks.

Table 4. Human Exposure Routes and Health Implications

| Route | Source | Potential Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Ingestion | Food, water | Gastrointestinal effects |

| Inhalation | Airborne fibers | Respiratory stress |

| Dermal | Cosmetics | Limited evidence |

| Systemic | Nanoplastics | Immune disruption |

6.3 Knowledge Gaps

Despite increasing evidence of exposure, the long-term health consequences of chronic microplastic exposure remain poorly understood. Variability in particle size, polymer composition, and surface chemistry complicates risk assessment.

7. Nanoplastics as an Emerging Risk

Further fragmentation of microplastics produces nanoplastics (<1 µm), which exhibit enhanced bioavailability and reactivity. Nanoplastics can penetrate cellular membranes and interact with subcellular structures, but their detection and quantification remain technically challenging.

8. Mitigation Strategies and Policy Responses

Regulatory measures, including microbead bans, single-use plastic restrictions, and extended producer responsibility frameworks, have been implemented in several regions. Technological innovations such as biodegradable materials and advanced wastewater filtration systems offer potential mitigation strategies. Standardization of analytical methods remains a critical research priority.

10. Conclusion

Microplastics constitute a persistent and globally distributed form of environmental pollution with complex ecological and potential human health implications. Their ubiquity across environmental compartments reflects systemic failures in plastic production, consumption, and waste management. Addressing microplastic pollution requires integrated scientific research, regulatory intervention, industrial innovation, and societal behavioral change. Continued interdisciplinary efforts are essential to elucidate long-term risks and develop effective mitigation strategies.