The cardiovascular system is a complex network responsible for transporting blood throughout the body. This system includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood, all working together to circulate vital substances, such as oxygen, nutrients, and hormones, to tissues and organs. Additionally, it facilitates the removal of metabolic waste products like carbon dioxide and urea. The heart serves as the pump, and the blood vessels (arteries, veins, and capillaries) form the transport routes for the blood. The movement and pressure of blood within the cardiovascular system are tightly regulated to ensure homeostasis.

Blood Vessels and Their Function

Blood vessels are the highways of the cardiovascular system, directing blood flow to various parts of the body, where gases, nutrients, and waste products are exchanged between the blood and tissues. Their primary functions include:

- Transport: Blood vessels ensure that oxygenated blood from the lungs reaches the tissues and deoxygenated blood returns to the heart and lungs for reoxygenation.

- Regulation: Blood vessels regulate blood flow by constricting or dilating to ensure the proper distribution of blood to active tissues.

- Blood Pressure Control: Blood vessels play a significant role in controlling blood pressure by altering their diameter in response to physiological needs.

- Chemical Secretion: Blood vessels can secrete hormones and other substances that affect blood pressure and volume.

The Circulatory Pathways

The blood circulates through two main circuits:

- Pulmonary Circuit: This circuit carries blood between the heart and the lungs. Oxygen-depleted blood is pumped from the right side of the heart to the lungs, where it picks up oxygen and releases carbon dioxide. Oxygenated blood is then returned to the left side of the heart.

- Systemic Circuit: This circuit transports oxygenated blood from the heart to the rest of the body, delivering nutrients and oxygen to tissues. Deoxygenated blood is then returned to the heart for reoxygenation in the lungs.

Each of these circuits consists of three main types of blood vessels: arteries, veins, and capillaries.

Types of Blood Vessels

Arteries

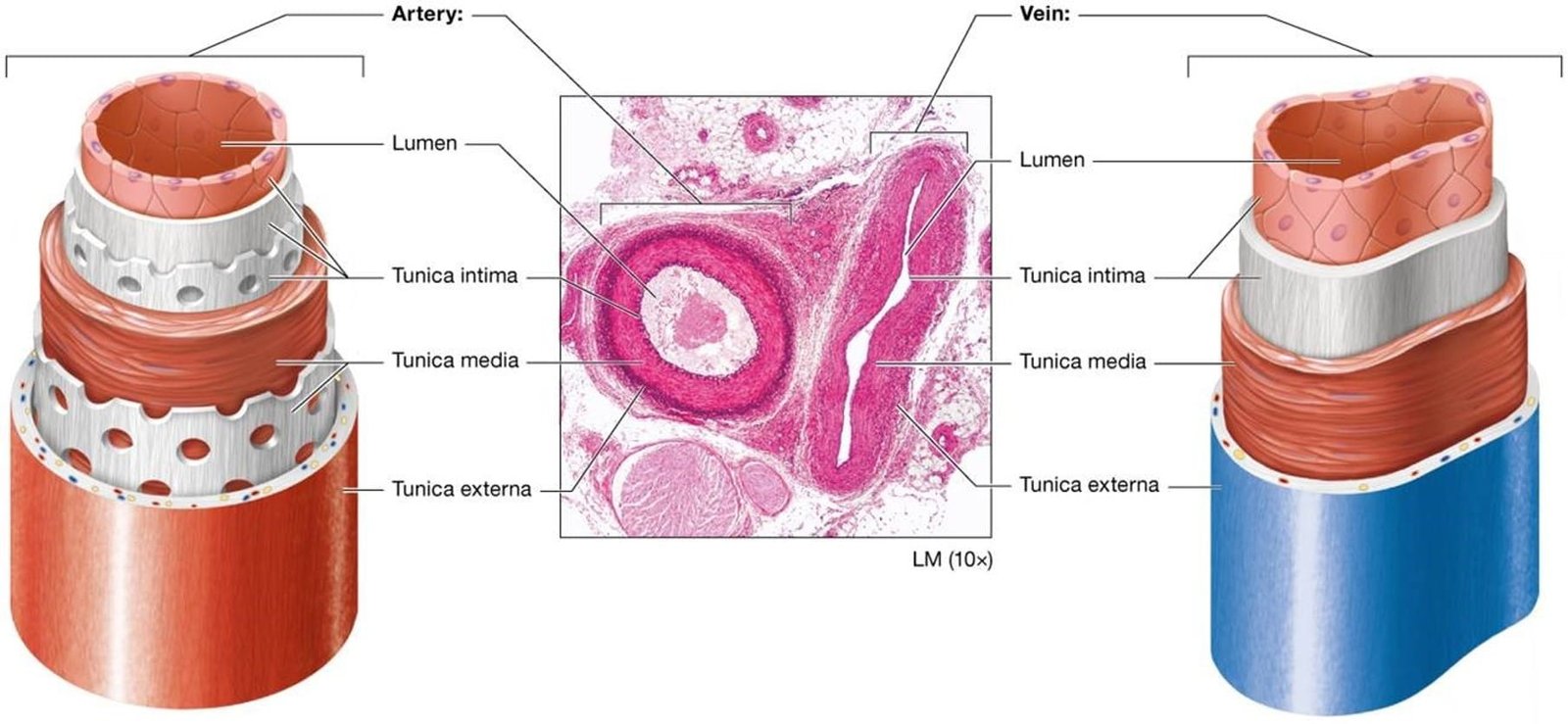

Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart to the body’s tissues. They typically carry oxygen-rich blood, except in the case of the pulmonary and fetal circulations, where they carry deoxygenated blood. Arteries have thick, muscular, and elastic walls to withstand the high pressure exerted as blood is pumped from the heart.

Characteristics of Arteries

- Thick muscular walls due to the need to endure high pressure from the heart’s pumping action.

- Smaller lumen (internal diameter) compared to veins.

- No valves: Arteries do not contain valves since the pressure from the heart prevents backflow.

- Elasticity: Arteries have more elastic tissue to allow them to stretch when blood is pumped through and recoil to maintain pressure during the relaxation phase of the heart.

Arteries can be classified into three types based on their size, structure, and function:

- Elastic Arteries: These are the largest arteries, such as the aorta and pulmonary trunk. Their function is to conduct blood from the heart to smaller arteries. The elastic tissue in their walls allows them to stretch under pressure and recoil to push the blood forward.

- Muscular Arteries: These arteries are medium-sized and have a well-developed smooth muscle layer. They distribute blood to various organs and tissues. Examples include the femoral artery and coronary arteries.

- Arterioles: These are the smallest arteries, which lead into capillaries. Arterioles play a critical role in regulating blood flow and pressure by constricting or dilating to adjust blood volume to different organs.

Veins

Veins are responsible for carrying blood back to the heart. They typically transport deoxygenated blood, except in the pulmonary and fetal circulations, where veins carry oxygen-rich blood. The pressure in veins is much lower than in arteries, and veins rely on muscle contractions, gravity, and valves to return blood to the heart.

Characteristics of Veins:

- Thinner walls compared to arteries, as the pressure inside veins is much lower.

- Larger lumen to accommodate the low-pressure blood flow and to hold a greater volume of blood.

- Valves: Many veins contain valves, especially in the legs, to prevent the backflow of blood as it returns to the heart.

- Less elastic tissue and smooth muscle than arteries, as veins do not need to withstand the same high pressures.

Veins are divided into two main types:

- Venules: These are small veins that collect blood from capillaries and join together to form larger veins.

- Large Veins: These veins are responsible for returning blood to the heart. Examples include the superior and inferior vena cavae, which bring deoxygenated blood into the right atrium of the heart.

Capillaries

Capillaries are the smallest and most numerous blood vessels, connecting arterioles to venules. They are where the exchange of gases, nutrients, and wastes occurs. Capillaries have extremely thin walls made of a single layer of endothelial cells to facilitate the rapid exchange of substances between the blood and the tissues.

Characteristics of Capillaries:

- Single layer of endothelial cells: This structure allows for the efficient exchange of oxygen, carbon dioxide, glucose, and other substances between the blood and surrounding tissues.

- Extensive network: Capillaries form vast networks within tissues, providing an enormous surface area for diffusion.

There are three main types of capillaries:

- Continuous Capillaries: These are the most common type, found in muscle, skin, and the nervous system. They allow the passage of small molecules, such as water and ions, but restrict larger molecules.

- Fenestrated Capillaries: These capillaries have small pores (fenestrations) that allow for the exchange of larger molecules and greater fluid volumes. They are found in areas like the kidneys, small intestine, and endocrine glands.

- Sinusoidal Capillaries: These are the leakiest capillaries, with larger gaps between endothelial cells. They are found in organs like the liver, spleen, and bone marrow, where the exchange of large molecules and even cells is necessary.

Blood Pressure and Circulatory Dynamics

Blood flow is primarily driven by pressure gradients within the blood vessels. The heart generates a high-pressure pulse of blood, which is transmitted through the arteries and gradually dissipates as blood moves into the arterioles and capillaries. The amount of blood flowing through the body at any given time is regulated by various factors, including resistance and the cross-sectional area of blood vessels.

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure is the force that the blood exerts on the walls of blood vessels. It is highest in the large arteries near the heart and decreases as blood moves through smaller arteries, arterioles, and capillaries. Blood pressure is expressed in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) and is typically measured using two values:

- Systolic Pressure: The pressure when the heart contracts and pumps blood into the arteries.

- Diastolic Pressure: The pressure when the heart relaxes and fills with blood.

A normal blood pressure reading is approximately 120/80 mm Hg. Hypertension, or high blood pressure, occurs when the systolic pressure is consistently above 140 mm Hg or the diastolic pressure is above 90 mm Hg. Conversely, hypotension, or low blood pressure, is when the systolic pressure is lower than 90 mm Hg or the diastolic pressure is lower than 60 mm Hg.

Resistance

Resistance is the opposition to blood flow in the circulatory system, primarily due to the friction between the blood and the walls of the blood vessels. Several factors contribute to resistance, including the size of the blood vessel, the viscosity of the blood, and the overall length of the vessels. Resistance is inversely proportional to the diameter of the blood vessel—narrower vessels cause more resistance, which raises blood pressure, while dilated vessels lower resistance and blood pressure.

Regulation of Blood Pressure

Blood pressure is regulated by both short-term and long-term mechanisms. The short-term regulation occurs through the nervous system, especially through the baroreceptor reflex. Baroreceptors are stretch receptors located in large arteries like the aorta and carotid arteries. When they detect changes in blood pressure, they send signals to the brain to adjust the heart rate and vessel diameter.

Long-term regulation is managed by the kidneys and the endocrine system. Hormones such as epinephrine, angiotensin II, and aldosterone help adjust blood pressure by causing vasoconstriction or fluid retention. Conversely, hormones like atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) cause vasodilation and help lower blood pressure.

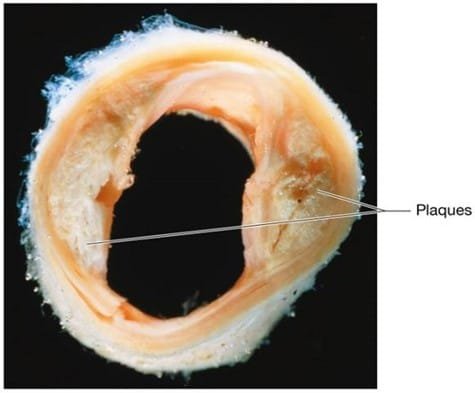

Atherosclerosis and Its Effects

Atherosclerosis is a condition where fatty deposits (plaques) build up inside the walls of arteries, leading to narrowing and hardening of the vessels. This condition primarily affects medium- and large-sized arteries and can increase the risk of heart attacks, strokes, and other cardiovascular diseases. Plaques tend to form in areas where blood flow is turbulent, such as at branch points or where arteries curve.

Atherosclerosis is often caused by high cholesterol, smoking, hypertension, and diabetes. Over time, plaques can rupture, leading to blood clots that may completely block blood flow, resulting in tissue damage or organ failure.

Venous Disorders

Varicose Veins are a common venous disorder characterized by swollen, twisted veins, usually in the legs. This condition occurs when the valves in veins become weakened or damaged, leading to blood pooling and vein enlargement. Varicose veins are often caused by prolonged standing, pregnancy, obesity, or aging. The veins become stretched and rope-like, and in some cases, they may be painful.

Conclusion

The cardiovascular system is a critical component of human physiology, responsible for transporting blood, nutrients, and waste products throughout the body. Blood vessels, including arteries, veins, and capillaries, work in unison to ensure that blood circulates efficiently and effectively. Proper regulation of blood pressure, blood flow, and resistance is essential for maintaining homeostasis. Disorders like atherosclerosis, hypertension, and varicose veins can significantly impact the cardiovascular system and require attention to prevent serious health consequences.

Understanding the structure and function of the cardiovascular system is essential for diagnosing, treating, and preventing cardiovascular diseases, which remain a leading cause of death worldwide.