DNA sequencing is one of the most important techniques in modern biological sciences. From identifying a single mutation in a gene to validating cloned DNA fragments, sequencing allows scientists to read the exact order of nucleotides in DNA. Among the many sequencing technologies available today, Sanger sequencing remains a gold standard for accuracy, reliability, and simplicity—especially in educational labs and small-scale research.

This student-friendly guide explains what Sanger sequencing is, how it works, its historical importance, its challenges, and why it is still widely used today.

What Is DNA Sequencing and Why Is It Important?

DNA sequencing refers to the process of determining the precise order of nucleotides—adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G)—within a DNA molecule. Understanding DNA sequences helps researchers:

Identify mutations in genes

Study genetic diseases

Analyze cloned DNA fragments

Understand gene function and regulation

Perform whole-genome sequencing of organisms

While modern next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies can sequence entire genomes rapidly, traditional sequencing methods laid the foundation for all advances in genomics.

Historical Background: The Birth of Sanger Sequencing

DNA sequencing was not always as accessible as it is today. In 1977, Frederick Sanger and his collaborators developed a revolutionary approach known as the chain termination method, or Sanger sequencing. This method made it possible to decode DNA sequences accurately for the first time.

At the same time, another method called the Maxam–Gilbert sequencing method existed. However, due to its complexity and use of hazardous chemicals, Maxam–Gilbert sequencing gradually fell out of favor. Sanger sequencing, on the other hand, became widely adopted and remains relevant even today.

Principle of Sanger Sequencing (Chain Termination Method)

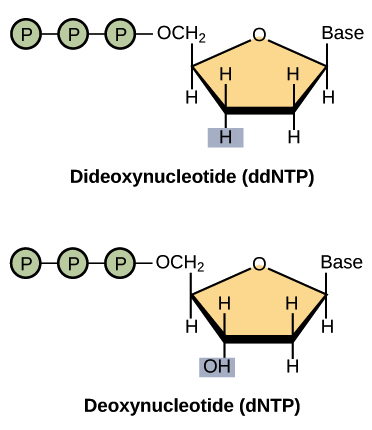

Sanger sequencing is also called dideoxynucleotide sequencing because it relies on special modified nucleotides known as dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs).

Key Components Required in Sanger Sequencing

Template DNA (usually PCR-amplified)

A single primer

DNA polymerase

Normal nucleotides (dNTPs)

Modified nucleotides (ddNTPs), each labeled with a unique fluorescent dye

The critical feature of ddNTPs is that they lack a hydroxyl (–OH) group, which is essential for forming phosphodiester bonds. Once a ddNTP is incorporated, DNA synthesis stops.

Step-by-Step Process of Sanger Sequencing

1. DNA Denaturation

The double-stranded DNA template is first denatured into single strands so it can be copied.

2. Primer Binding

A short primer binds to a specific primer binding site on the template DNA. This defines where sequencing begins.

3. DNA Synthesis and Chain Termination

DNA polymerase starts extending the new DNA strand by adding dNTPs. Occasionally, a fluorescently labeled ddNTP is incorporated instead of a dNTP. Since ddNTPs lack the hydroxyl group, DNA synthesis terminates at that point.

4. Generation of DNA Fragments

This process produces a mixture of DNA fragments of varying lengths, each ending with a labeled ddNTP corresponding to A, T, G, or C.

5. Capillary Gel Electrophoresis

The fragments are separated by size using capillary gel electrophoresis. Smaller fragments move faster than larger ones.

6. Electropherogram Analysis

As fragments pass a detector, the fluorescent labels emit signals. These signals are recorded as an electropherogram, and automated software translates them into a readable DNA sequence.

Understanding the Electropherogram

An electropherogram is a graphical output showing colored peaks, each representing a nucleotide. Students often learn to:

Read peak order to determine the DNA sequence

Identify low-quality regions

Detect mutations or base substitutions

This visual output makes Sanger sequencing particularly useful for teaching molecular biology concepts.

Challenges of Sanger Sequencing

Despite its accuracy, Sanger sequencing has several limitations:

1. Limited Read Length

Sanger sequencing can sequence only 300–1000 base pairs (bp) in a single run. This makes it unsuitable for large-scale projects like whole-genome sequencing.

2. Poor Quality at Primer Binding Site

The first 15–40 nucleotides near the primer binding site often have poor signal quality, making sequence interpretation difficult in this region.

3. Low Throughput

Compared to next-generation sequencing, Sanger sequencing is slower and cannot process large numbers of samples simultaneously.

Present-Day Applications of Sanger Sequencing

Even with advanced sequencing technologies available, Sanger sequencing continues to play an important role.

1. Small-Scale Targeted Sequencing

Sanger sequencing is ideal for analyzing:

Single genes

Specific mutations

Short DNA fragments

2. Validation of NGS Results

Many laboratories use Sanger sequencing to confirm mutations detected by high-throughput sequencing methods.

3. Cloned DNA Fragment Analysis

It is widely used to verify cloned inserts in plasmids during molecular cloning experiments.

4. Clinical and Diagnostic Use

Due to its reliability, Sanger sequencing is still used in diagnostic settings where accuracy is critical.

Why Is Sanger Sequencing Still Relevant Today?

The original method has evolved into a semi-automated technique that is faster, more accurate, and easier to use. Key reasons for its continued use include:

High accuracy

Simple workflow

Clear data interpretation

Cost-effectiveness for small projects

Strong educational value for students

For many teaching laboratories, Sanger sequencing serves as an excellent introduction to DNA sequencing principles.

Conclusion

Sanger sequencing is a cornerstone of molecular biology and genetics. Developed by Frederick Sanger in 1977, this chain termination method revolutionized the way scientists read DNA. While it has limitations such as shorter read length and lower throughput, its simplicity, precision, and reliability ensure its continued relevance.

For students, understanding Sanger sequencing provides essential insight into how DNA sequencing works at a fundamental level. Even in the era of whole-genome sequencing, Sanger sequencing remains a powerful and indispensable tool in biological sciences.

Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) Technology : Advancements, Platforms, and Applications