Introduction

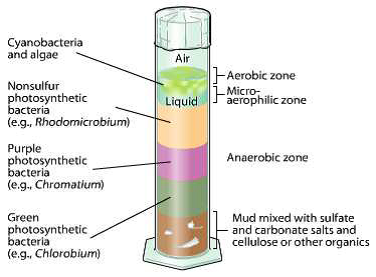

The Winogradsky column is one of the most powerful and visually engaging tools used in microbiology and environmental science to study microbial diversity, metabolism, and ecological interactions. It is a miniature, self-contained ecosystem that allows microorganisms from natural sediments to grow, interact, and organize themselves into visible layers over time. Each layer represents a distinct microbial community adapted to specific chemical conditions.

Originally developed in the 1880s by Russian microbiologist Sergei Winogradsky, this technique transformed the way scientists understand microorganisms. Instead of studying microbes in isolation, the Winogradsky column highlights how microorganisms depend on one another and how they drive Earth’s biogeochemical cycles, including the carbon, sulfur, nitrogen, and iron cycles.

Today, the Winogradsky column is widely used in student laboratories, classrooms, and research settings because it demonstrates complex ecological principles using simple materials.

Why the Winogradsky Column Is Scientifically Important

The Problem of “Unculturable” Microorganisms

The vast majority of microorganisms on Earth are considered unculturable using standard laboratory techniques. This means they cannot grow on petri dishes or in test tubes under artificial conditions. There are several reasons for this:

Many microbes rely on metabolites produced by neighboring organisms

Some require very specific oxygen, light, or chemical gradients

Others grow slowly and are outcompeted in artificial media

The Winogradsky column overcomes these limitations by closely mimicking natural sediment environments. Instead of forcing microbes to grow alone, it allows them to develop within a complex, interacting community, making it possible to study organisms that would otherwise remain invisible.

Microbial Succession: Life Changes Over Time

What Is Microbial Succession?

Microbial succession refers to the sequential appearance and replacement of microbial communities as environmental conditions change. In a Winogradsky column, succession occurs because microorganisms continuously modify their surroundings as they grow.

For example:

Early microbes consume easily available nutrients

Their activity depletes oxygen or produces waste products

New microbes that can use these byproducts begin to thrive

This step-by-step transformation of the ecosystem mirrors what happens in ponds, wetlands, soils, and sediments across the planet.

Environmental Gradients in a Winogradsky Column

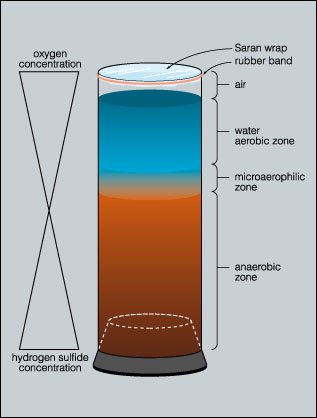

As the column matures, two major chemical gradients form:

Oxygen (O₂) Gradient

High oxygen levels at the top

Gradual decrease with depth

No oxygen in the bottom anaerobic zone

Hydrogen Sulfide (H₂S) Gradient

High sulfide concentration at the bottom

Decreases upward

Nearly absent near the surface

Microorganisms arrange themselves precisely along these gradients, growing where conditions are optimal for their metabolism.

How a Winogradsky Column Is Constructed

A Winogradsky column is built using mud and water from the same natural habitat, such as a pond, marsh, wetland, or stream. These sediments already contain a diverse microbial community.

Additional materials are added to support microbial growth:

Cellulose (shredded newspaper) as a carbon source

Sulfur (egg yolk or calcium sulfate) for sulfur metabolism

Light to support photosynthetic organisms

A transparent container to observe microbial layers

Once assembled, the column is incubated for 4–8 weeks, during which colorful microbial layers slowly appear.

Microbial Layers in a Winogradsky Column

Each visible layer in the column represents a distinct functional group of microorganisms, organized from top to bottom based on oxygen and sulfide availability.

Table: Major Microbial Groups in a Classical Winogradsky Column

| Position in Column | Functional Group | Example Organisms | Visual Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top | Photosynthesizers | Cyanobacteria | Green or reddish-brown layer; oxygen bubbles |

| Upper layers | Nonphotosynthetic sulfur oxidizers | Beggiatoa, Thiobacillus | White filaments |

| Upper middle | Purple nonsulfur bacteria | Rhodospirillum, Rhodopseudomonas | Red, orange, or brown |

| Middle | Purple sulfur bacteria | Chromatium | Purple or purple-red |

| Lower middle | Green sulfur bacteria | Chlorobium | Green layer |

| Bottom | Sulfate-reducing bacteria | Desulfovibrio, Desulfobacter | Black sediment |

| Bottom | Methanogens | Methanococcus, Methanosarcina | Methane bubbles |

What Happens in Each Layer?

Top Layer: Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria perform oxygenic photosynthesis, producing oxygen as a byproduct. Oxygen bubbles often form in this layer, creating the aerobic zone of the column.

Middle Layers: Sulfur Bacteria

Purple and green sulfur bacteria use sulfide instead of water during photosynthesis

Purple nonsulfur bacteria use organic acids rather than sulfide

These organisms thrive where light, sulfide, and low oxygen overlap

Bottom Layer: Anaerobic Microorganisms

Sulfate-reducing bacteria break down organic acids and produce hydrogen sulfide

Methanogens produce methane gas from organic matter

Black sediment indicates iron sulfide formation

Step-by-Step Procedure for Building a Winogradsky Column

Materials Needed

Shovel, bucket, and sample bottle

Transparent 1-liter container

Mixing bowls and spoon

Egg yolk or calcium sulfate

Shredded newspaper

Plastic wrap and rubber band

Light source

Assembly Steps

Collect saturated mud and water from the same habitat

Remove rocks and debris

Mix mud with water until smooth

Add egg yolk and newspaper to one portion

Fill the column:

Bottom ¼: enriched mud

Middle ½: regular mud

Top: water

Seal and incubate in light at room temperature

Observe weekly for 4–8 weeks

Optional Experimental Modifications

Winogradsky columns are highly customizable and ideal for experimentation:

Salt addition → enriches halophiles

Iron (nail or steel wool) → selects iron-oxidizing bacteria

Temperature changes → select thermophiles or psychrophiles

Light intensity variation → affects photosynthetic growth

Colored cellophane → tests wavelength-dependent photosynthesis

Dark incubation → suppresses all photosynthetic organisms

Observing and Analyzing Results

After several weeks:

Light-incubated columns develop green, purple, and red layers

Dark-incubated columns lack photosynthetic layers

Black sediment still forms due to sulfate reducers

Environmental factors such as sediment porosity, sulfate availability, and microbial diversity strongly influence the final appearance of each column.

Educational Value of the Winogradsky Column

The Winogradsky column is widely used to teach:

Microbial ecology

Anaerobic vs aerobic metabolism

Biogeochemical cycles

Ecosystem interdependence

Environmental gradients

It is particularly effective because students can see microbial processes happening in real time, making abstract concepts tangible and memorable.

Summary and Key Takeaways

The Winogradsky column is a powerful demonstration of how microbial life organizes itself in response to chemical gradients and environmental change. By recreating a natural sediment ecosystem, it allows students to observe microbial succession, sulfur cycling, and ecological cooperation within a single transparent container.

This experiment highlights the importance of microorganisms in shaping Earth’s environments and emphasizes that life rarely exists in isolation. Instead, microbial communities function as interconnected systems that sustain global biogeochemical proccess.