C3 glomerulopathy (C3G) is a rare and complex kidney disorder caused by the dysregulation of the immune system’s complement pathway, which plays a crucial role in defending the body against infections. This disorder primarily affects the glomeruli, which are clusters of tiny blood vessels in the kidneys responsible for filtering waste and excess fluids from the bloodstream. Overactivation of the complement system leads to kidney damage, and C3G can ultimately result in kidney failure if left untreated. In this article, we’ll explore the causes, frequency, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of C3 glomerulopathy, along with a case study that highlights its clinical complexities.

Synonyms: C3G, Glomerulonephritis with Dominant C3

What is C3 Glomerulopathy?

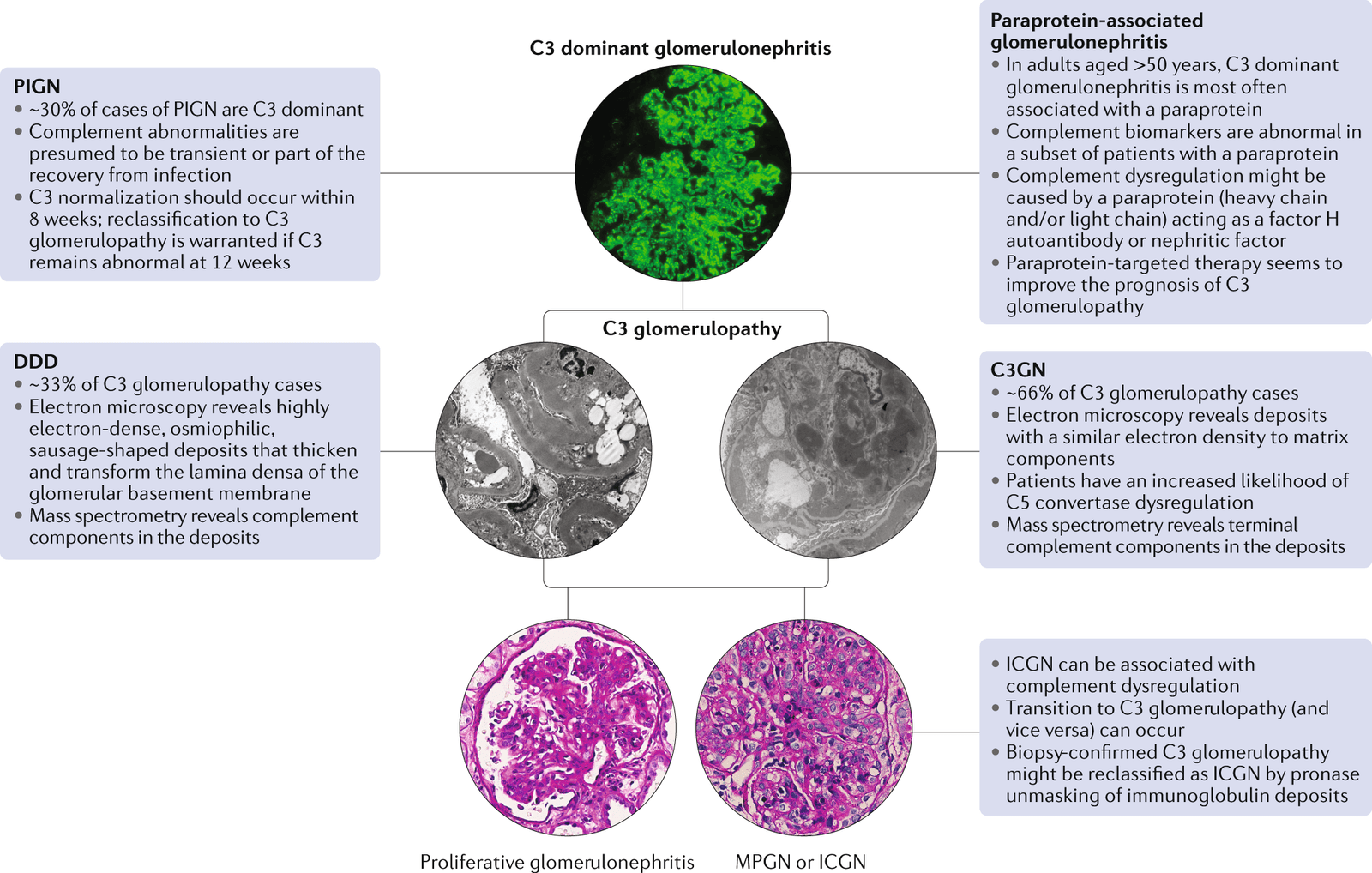

C3 glomerulopathy is an umbrella term for a group of kidney diseases that arise from dysfunction in the complement system, a part of the immune response. The two main forms of C3 glomerulopathy are Dense Deposit Disease (DDD) and C3 Glomerulonephritis (C3GN). Both conditions share common features, but they present in different age groups. Dense Deposit Disease is more commonly found in children, while C3 Glomerulonephritis is typically diagnosed in older adults. Despite differences in age of onset, both conditions result in damage to the glomeruli, leading to inflammation, proteinuria (excess protein in the urine), hematuria (blood in the urine), hypertension (high blood pressure), and progressive kidney dysfunction.

C3G is notorious for its high recurrence rate, which significantly increases the risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), especially in patients with Dense Deposit Disease. The disorder is also linked to a variety of other health complications, particularly in older patients. Studies have found that C3G is strongly associated with monoclonal gammopathy in individuals over the age of 50 and is more likely to recur after kidney transplantation.

Causes of C3 Glomerulopathy

The root cause of C3 glomerulopathy lies in genetic mutations that disrupt the regulation of the complement system. The complement system consists of a group of proteins that work together to defend against foreign invaders like bacteria and viruses, remove damaged cells, and trigger inflammation. When functioning properly, the complement system is carefully regulated to ensure it targets harmful invaders without attacking healthy tissues.

In many cases of C3 glomerulopathy, genetic mutations in complement-related genes contribute to an overactive complement system, leading to kidney damage. A mutation in the CFHR5 gene, for example, has been associated with C3 glomerulopathy in individuals from Cyprus. Other mutations, such as in the C3 and CFH genes, have been identified in different populations, though these mutations account for only a small percentage of all cases.

In addition to genetic mutations, certain genetic variations—called polymorphisms—are associated with an increased risk of developing C3 glomerulopathy. The presence of a particular combination of these genetic variants can make individuals more susceptible to the disease, though not everyone with these genetic changes will develop the condition.

Overactivation of the complement system results in damage to the glomeruli, the small blood vessels in the kidneys that filter waste from the blood. When the glomeruli are damaged, they can no longer perform their vital role, leading to kidney dysfunction. In addition to kidney damage, this overactive complement response is also linked to other health problems, such as acquired partial lipodystrophy (a condition involving abnormal fat distribution) and the buildup of drusen in the retina (a marker for eye disease).

Frequency of C3 Glomerulopathy

C3 glomerulopathy is extremely rare, with an estimated prevalence of 1 to 2 cases per million people worldwide. Interestingly, it is equally common in both men and women, though it primarily affects people with specific genetic predispositions. Due to its rarity, many healthcare professionals may not immediately recognize C3 glomerulopathy, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

Pathophysiology of C3 Glomerulopathy

In most cases of C3 glomerulopathy, the disease is driven by the presence of autoantibodies, particularly C3 nephritic factors (C3NeFs). These autoantibodies bind to C3-convertase (C3bBb), a critical protein complex in the alternative complement pathway, and prevent it from being regulated by the body’s normal control mechanisms. This disruption results in the continuous activation of the complement system, which leads to the excessive deposition of C3 in the glomeruli, further damaging the kidneys.

While the majority of C3 glomerulopathy cases are caused by autoantibodies, a smaller percentage—around 10-15%—are linked to mutations in complement proteins, such as C3, Factor B, Factor H, and Factor I. Laboratory tests can help distinguish between these two causes by identifying the presence or absence of C3 nephritic factors.

Management of C3 Glomerulopathy

Currently, there is no definitive cure for C3 glomerulopathy, but several treatment strategies are used to manage the disease and its complications. The goal of treatment is to control the overactive complement system, reduce inflammation, and slow the progression of kidney damage.

- Symptomatic Treatment: Many patients with C3 glomerulopathy are treated with nonspecific therapies commonly used for other chronic kidney diseases, including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and lipid-lowering medications. These treatments help manage high blood pressure, proteinuria, and lipid abnormalities associated with the disease.

- Complement Inhibition: A promising area of treatment for C3 glomerulopathy is complement inhibition. Drugs that block the complement system, such as terminal pathway blockers, may help reduce the activation of complement and slow disease progression. While complement inhibition has shown some success in certain patients, it is not universally effective.

- Dialysis and Kidney Transplantation: For patients who develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD) due to C3 glomerulopathy, treatment options are limited to dialysis or kidney transplantation. Unfortunately, C3 glomerulopathy tends to recur in nearly all kidney transplants, often leading to graft failure in 50-90% of transplant recipients.

- Plasma Replacement Therapy: In patients with mutations in the CFH gene, plasma replacement therapy may help control complement activation and slow the progression of kidney failure.

- Surveillance: Regular monitoring of kidney function is essential for patients with C3 glomerulopathy, particularly those at risk of progressing to ESRD. Nephrologists familiar with C3G should conduct biannual assessments of the complement pathway and periodic eye examinations to monitor for associated retinal problems.

Diagnosis of C3 Glomerulopathy

Diagnosing C3 glomerulopathy involves a combination of clinical suspicion, laboratory tests, and renal biopsy. A key diagnostic feature of C3G is the presence of low levels of complement component C3 in the blood, known as hypocomplementemia.

- Renal Biopsy: The gold standard for diagnosing C3 glomerulopathy is a renal biopsy, which allows pathologists to examine kidney tissue under a microscope and assess the extent of glomerular damage. The biopsy can also help distinguish between C3 glomerulonephritis and dense deposit disease. Immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy reveals bright staining for C3, which is a hallmark of C3 glomerulopathy.

- Electron Microscopy (EM): EM is crucial for distinguishing between C3GN and DDD, as the two conditions have distinct patterns of glomerular deposits. C3GN typically shows light, hump-like deposits, while DDD shows dense, ribbon-like deposits in the glomerular basement membrane.

- Molecular Genetic Testing: Genetic testing can be helpful in identifying pathogenic variants in complement-related genes. This may aid in confirming the diagnosis, determining the cause of the disease, and guiding treatment decisions.

Case Study: C3 Glomerulopathy Post-Kidney Transplant

A 78-year-old man with chronic kidney disease recently received a kidney transplant. Initially, his renal function improved, but during a follow-up visit, his kidney function began to deteriorate rapidly. After being treated with methylprednisolone for suspected acute rejection, there was no improvement. A kidney biopsy revealed predominant C3 deposits, leading to a diagnosis of C3 glomerulonephritis (C3GN). Despite receiving eculizumab, a complement inhibitor, there was no clinical improvement, and the patient was placed on hemodialysis. This case highlights the challenges of managing C3G, particularly when it recurs after kidney transplantation.

Inheritance and Genetic Considerations

Most cases of C3 glomerulopathy occur sporadically, meaning they are not inherited from family members. However, some families have multiple members affected by the disease, and there may be a connection between C3 glomerulopathy and autoimmune diseases, which involve the immune system attacking the body’s tissues. The exact relationship between C3G and autoimmune diseases is still under investigation.

Conclusion

C3 glomerulopathy is a rare but serious kidney disease caused by the overactivation of the complement system. While there is no cure, early diagnosis and management are crucial for slowing disease progression and improving patient outcomes. Physicians should consider C3G in patients with unexplained kidney dysfunction, particularly those with a history of autoimmune disease or kidney transplant. Ongoing research into complement inhibition and genetic testing will hopefully provide new therapeutic options in the future.

References

- Miller, L. E., & Stevens, C. D. (2021). Clinical immunology and Serology: A laboratory perspective. F.A. Davis Company.

- Ponticelli, C., Calatroni, M., & Moroni, G. (2023). C3 glomerulopathies: Dense deposit disease and C3 glomerulonephritis. Frontiers in Medicine, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1289812

- Ruiz-Fuentes, M. C., Caba-Molina, M., Polo-Moyano, A., Palomares-Bayo, M., Galindo-Sacristan, P., & De Gracia-Guindo, C. (2023).

- A 78-year-old man with chronic kidney disease and monoclonal gammopathy who developed post-transplant C3 glomerulopathy – recurrence or de novo? A case report and literature review. American Journal of Case Reports, 24. https://doi.org/10.12659/ajcr.939726

- Smith, R.J.H., Appel, G.B., Blom, A.M. et al. C3 glomerulopathy — understanding a rare complement-driven renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 15, 129–143 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-018-0107-2