Papovaviruses is a term combining papilloma viruses (PA), polyoma viruses (PO), and vacuolating agents (VA). The name “papova” comes from “papillae,” referring to bumps, growths, or pimples, and “oma,” which means tumor. Historically, these viruses were classified under the Family Papovaviridae, but this classification is no longer recognized. The viruses are now divided into two distinct families: human papillomaviruses (HPV), and human polyomaviruses.

- Papillomaviridae: The family of human papillomaviruses (HPV)

- Polyomaviridae: The family of human polyomaviruses

The vacuolating agents are also classified under the Polyomaviridae family, which is a group of viruses that share certain characteristics. Both papillomaviruses and polyomaviruses are DNA viruses that are naked viruses, meaning they lack an envelope. This characteristic makes them more stable in the environment and easier to transmit through direct or indirect contact.

Human Papillomaviruses (HPV)

Human Papillomaviruses (HPV) are a group of more than 200 related viruses that primarily infect the skin and mucous membranes, such as the genitals, mouth, and throat. HPV infection occurs in the dividing epidermal cells or basal layer cells of the skin, where the virus enters the cells and begins replicating. HPV is highly host-specific and tissue-specific, meaning it typically infects one species and targets specific types of tissue.

One of the challenges in studying HPV is that it cannot be cultured in laboratory conditions. It only grows in proliferating stratified squamous epithelial cells, which are difficult to grow outside of the body. This means that traditional cell culture methods for isolating viruses are not applicable to HPV. Consequently, detection of HPV infections relies on other techniques, such as immunoassays and genetic probes.

Detection of HPV

Since HPV cannot be cultured, detection focuses on identifying the virus’s genetic material in infected cells. This can be done through methods like DNA hybridization (PCR, Southern Blot Hybridization) or in situ hybridization. Mucosal smears (e.g., from the cervix, vagina, or anus) are commonly used for testing, and Pap smear tests often incorporate HPV testing to detect the presence of HPV and identify specific strains.

One notable limitation is that, as of now, there is no test available to detect HPV in male specimens. However, it is well-documented that men can develop genital warts due to HPV infection, although the development of cancer is rare compared to women. Males are considered the vectors of HPV transmission, including the spread between women who have sex with women (WSW).

Types of Human Papillomaviruses HPV

HPV types are classified based on their tissue tropism, or preference for infecting certain types of tissues. HPV types are categorized into two broad groups:

- Cutaneous types: These primarily infect the skin and cause common warts.

- Mucosal types: These infect the mucous membranes and are associated with genital warts, as well as cervical cancer.

Among the mucosal types, over 40 HPV types are sexually transmitted, and these are designated as genital types. These types are further classified based on their association with genital tract cancers as:

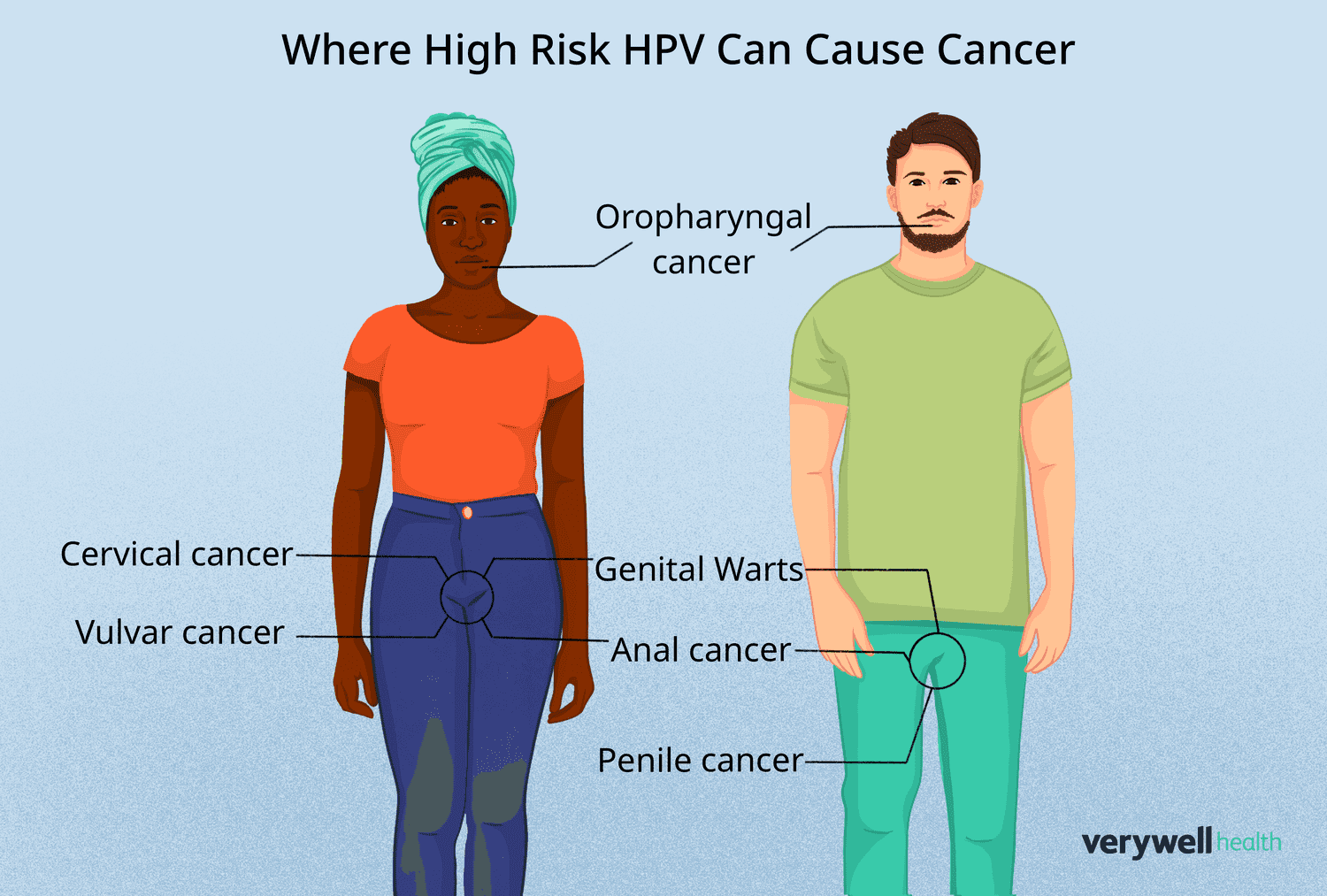

- High-risk types: HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 56, 58, 59, and 68 are associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer and other cancers.

- Low-risk types: HPV 6 and 11 are primarily responsible for genital warts and do not usually cause cancer.

- Intermediate-risk types: These types have been associated with lower-risk precancerous lesions but are not as commonly linked to cancer as high-risk types.

Cervical Cancer and HPV

One of the most significant medical concerns related to HPV is its strong association with cervical cancer. Cervical cancer is the third most common cancer in women worldwide, following breast and colorectal cancers. It is primarily caused by infection with high-risk types of HPV, particularly HPV 16 and 18, which are responsible for about 98% of cervical cancers.

In fact, over 50% of women contract a genital HPV infection within 2 years of becoming sexually active, and it is estimated that 80% of women will be infected with HPV during their lifetime. However, most infections are transient and asymptomatic, and the body’s immune system clears the virus without any long-term effects. In some cases, especially with high-risk HPV types, the infection persists and can lead to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), which is a precursor to cancer.

HPV and Other Cancers

While cervical cancer is the most well-known cancer associated with HPV, other cancers are also linked to the virus. Anal cancer is becoming more common, especially in men who have sex with men (MSM) and individuals with HIV. Although anal cancer is still less common than cervical cancer, its incidence is increasing.

HPV can also cause cancers of the oropharynx, including the throat, tonsils, and tongue, particularly in individuals who engage in oral sex. Studies have shown that an increased number of oral and vaginal sex partners, lack of condom use, and poor dental hygiene correlate with a higher risk of developing oropharyngeal cancer associated with HPV.

Risk Factors for Cervical Cancer

Several risk factors are associated with Human Papillomaviruses infection and the subsequent development of cervical cancer. These include:

- Number of sexual partners: Women with multiple sexual partners are at higher risk of contracting HPV.

- Age at first intercourse: Early initiation of sexual activity increases the risk of HPV exposure.

- Sexual activity of male partners: Male partners who have had multiple sexual partners may increase the risk of HPV transmission.

- Failure to use barrier contraception: Lack of condom use increases the likelihood of HPV transmission.

- Smoking: Tobacco use weakens the immune system and increases susceptibility to persistent HPV infections.

- Oral contraceptive use: Long-term use of birth control pills may increase the risk of cervical cancer, especially in women who smoke.

- Multiple pregnancies: Women who have had many pregnancies may have a higher risk of developing cervical cancer.

- Immunosuppression: Individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV, are more likely to develop persistent HPV infections.

HPV Diagnosis

Diagnosis of HPV infection often involves a combination of methods:

- Biopsy and Histology: Biopsy samples from abnormal tissues are examined to identify changes characteristic of HPV infection.

- Papanicolaou (Pap) Smear: This is a widely used screening tool that involves collecting cells from the cervix. If HPV is suspected, additional testing such as DNA testing (PCR, Southern Blot Hybridization) or in situ hybridization may be conducted.

Benign Lesions Caused by HPV

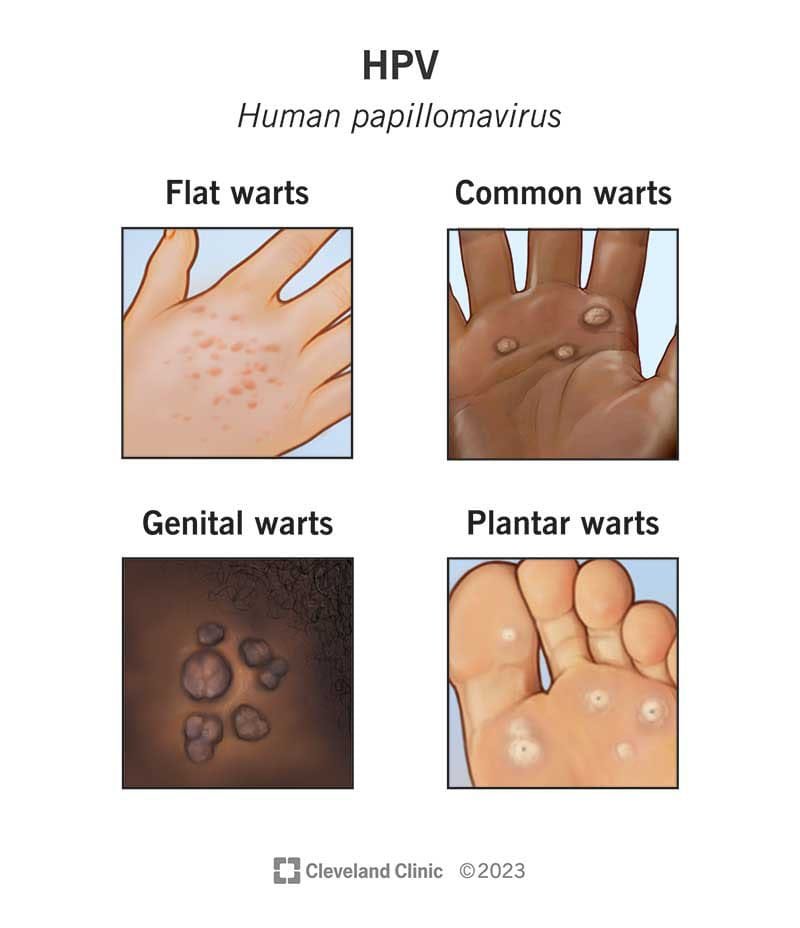

Many types of HPV infection lead to benign lesions that do not cause cancer but can be uncomfortable or cause cosmetic concerns. These include:

- Common Warts (Verruca Vulgaris): Characterized by rough, raised surfaces, commonly found on the hands, knees, and feet.

- Flat Warts (Verrucae Planae): Smoother and flatter than common warts, these are typically seen in children.

- Butcher’s Warts: Associated with butchers, but the reason for their occurrence in this occupation is not fully understood.

- Genital Warts (Condylomata Acuminata): Caused by HPV types 6 and 11, these warts are found on the genital and anal areas. They are typically benign but can be uncomfortable and cause complications during childbirth.

Malignant or Potentially Malignant Lesions

HPV can also lead to malignant or potentially malignant lesions, including:

- Bowenoid Papulosis: Multiple papules on the penis or vulva that resemble Bowen’s disease. These lesions may eventually become malignant.

- Intraepithelial Dysplasia: Abnormal changes in the epithelium, commonly referred to as CIN (Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia) in the cervix, VAIN (Vaginal Intraepithelial Neoplasia), and VIN (Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia). The most severe form of dysplasia, CIN 3, involves all layers of the epithelium and has a high chance of progressing to invasive cancer.

Vaccination and Prevention

The best way to prevent HPV-related diseases is through vaccination. The HPV vaccine is most effective when administered before sexual activity begins. The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for individuals between the ages of 11-12 (though vaccination can start at age 9). A 3-dose regimen is typically used:

- First dose: Given at the first appointment.

- Second dose: 1-2 months after the first dose.

- Third dose: 2 months after the second dose.

Available vaccines include:

- 2vHPV (Cervarix): Targets HPV 16 and 18 (approved for females only).

- 4vHPV (Gardasil): Targets HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 (approved for both males and females).

- 9vHPV (Gardasil-9): Targets 9 HPV types (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), and is available for both males and females.

These vaccines are prophylactic, meaning they prevent infection but do not treat existing infections.

Treatment and Management

Currently, there are no antiviral drugs available to treat HPV infections. Vaccines offer protection against pre-cancers and non-invasive cancers like cervical pre-cancers, but they do not cure active infections. Treatment for HPV-related warts and lesions often includes topical treatments, cryotherapy, or surgical removal.

Conclusion

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infections are a global public health issue, with substantial contributions to the development of cancers like cervical cancer. While there is no cure for existing HPV infections, preventive measures such as vaccination have been shown to reduce the incidence of HPV-related cancers. Comprehensive education, early detection, and vaccination are critical in reducing the burden of HPV on public health.